As writer/illustrator Terry Riley's hard work does deserve a doff of the cap, I'll get the wrongness out of the way first. A quick flip through this book will leave you with the impression that, while the content's pretty standard fare (a trip through the Mesozoic, stopping off to gawk at particularly big and odd-looking beasts along the way), Riley does basically know his stuff. As ever, closer inspection proves rewarding. Riley begins the book with a look at the earliest dinosaur discoveries which, according to him, were made by...Marry Anning.

For you see, in the world of Riley, ichthyosaurs are dinosaurs. As are plesiosaurs. And pterosaurs. Hence, the rather charming illustration of Little Miss Mary (above) is accompanied by the following facepalm-inducing text:

"The first complete skeleton of a dinosaur was found in 1811. The finder was a twelve-year-old British girl, Mary Anning, and the skeleton was that of an ichthyosaur...In later years, she found the first complete skeletons of two more dinosaurs, a plesiosaur and a pterodactyl."While acknowledging new ideas on dinosaurian metabolism and lifestyles, Riley also falls foul of the contemporary fondness for Linnaean taxonomy:

"All dinosaurs were thought to be reptiles, which are cold-blooded animals. Then a complete fossilised pterosaur discovered in 1971 showed that these creatures were covered in fur. This means that pterosaurs were not, as previously thought, flying reptiles. Having fur, they must have been warm-blooded animals and therefore have belonged to a completely different group of animals that could fly."But of course.

Such inaccuracies are particularly jarring as most of the book is carefully and thoughtfully written, and incorporates many relatively new discoveries (or at least, goes beyond the usual brontosaur/tyrannosaur/stegosaur triumvirate). Deinocheirus - the disembodied forelimb of which Riley illustrates alongside an especially dapper gentleman with Action Man hair - is such an inclusion, and one with a little topical resonance, I thought. Riley even goes as far as to describe birds as 'living dinosaurs', a notion scoffed at by some of the palaeontological 'old guard' at the time.

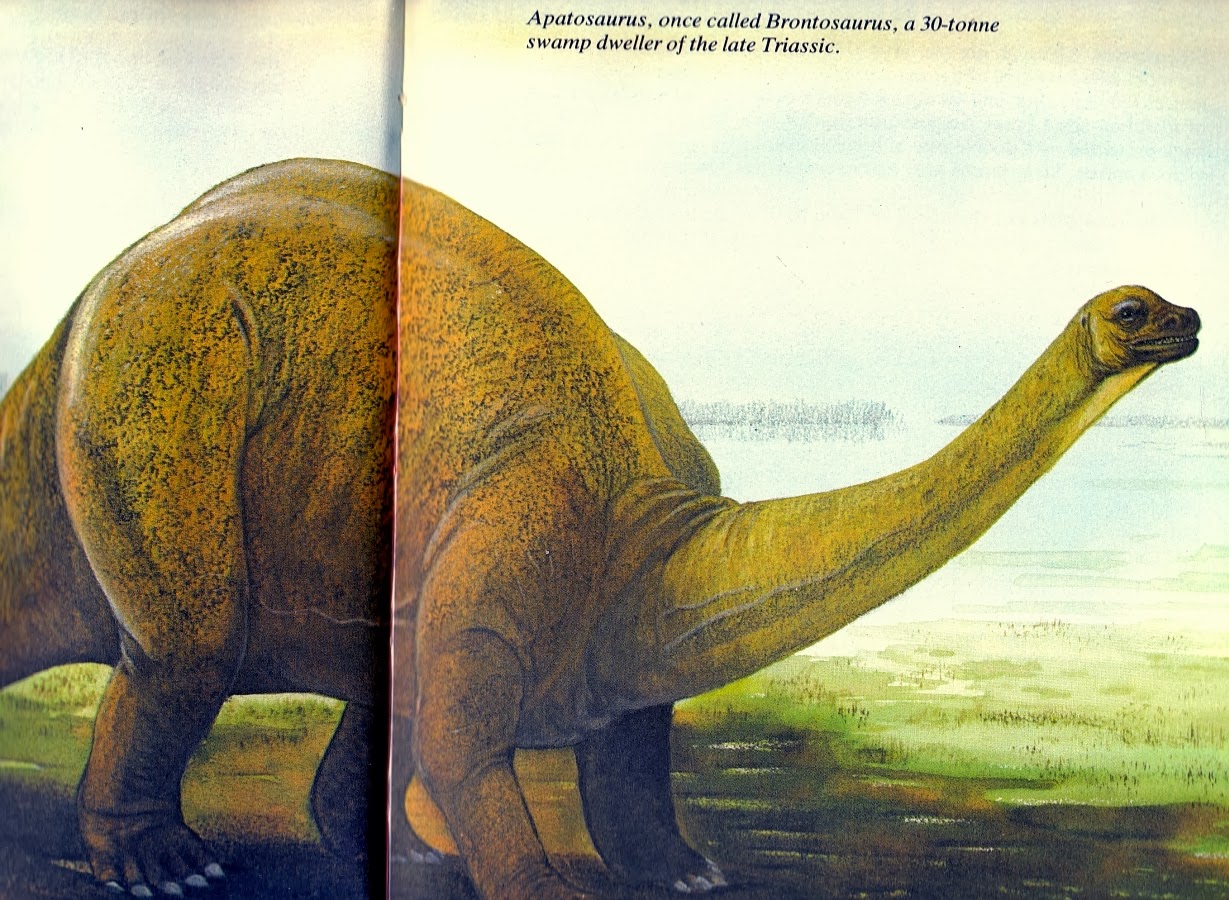

None of this is to say that the book doesn't have its fair share of outrageously retro bronto-blimps. Of course it bloody well does. Although depicted out on the shoreline, Riley's stodgy, stub-headed bronto is described as a "swamp dweller", and while Riley gains points for labelling the creature 'Apatosaurus', that "late Triassic" remark is unfortunate. I'm rather fond of the speckling on the beast's flanks, mind you. I shall name him Speckled Jim, a handsome and plump fellow.

By the same token, this ankylosaur (identified as "Ankylosaurus, or Euoplocephalus", because...meh) is very much of the old-fashioned, 'monstro armadillo louse' variety. I do enjoy Riley's penchant for a painterly, washy backdrop, which adds considerable charm to these pieces. I'll take vintage paintings like these over the latest execrable Pixel Shack abomination any day (GAG). Now if only I could persuade Dorling Kindersley likewise...

Occasionally, Riley's creations do stray from being conventionally retro, and start to look rather more...surreal. Such is the case with this Allosaurus, which appears to have suffered from a couple of ocular errors, namely

1. Size of eye does not account for scleral ring and surrounding tissue.

2. Eye is in the wrong hole.

Consequently, it looks a bit like John McLoughlin's attempt to restore Teratosaurus as a theropod dinosaur or alternatively, as Niroot would have it, a fish. A particularly sinister fish. Great pencil work, mind you. Why, if I could pencil that good, I wouldn't be sitting here with a glass of whisky, hammering out this load of old nonsense. I'd be flogging my super-artistic wares to enthusiastic publishers and collectors at fabulous prices. ('Cos that's how it works, right?)

Riley's Spinosaurus is somewhat more conventional-looking, but that of course means that it nevertheless looks bizarre by modern standards. There's something of a Neave Parker Megalosaurus air about it - the hunched posture, the tiny, grasping fingers, the perma-grumpy facial expression. It's just missing a discarded can being launched into the air by that right foot.

Sexy Rexy also appears quite Parkeresque, what with his upright posture and vacant stare, although the splayed legs have thankfully been ditched. The King, as he is known to his online fan community (although he died as the result of a cataclysmic asteroid strike, rather than on the throne), makes a rather more exciting appearance on the cover, which happily I haven't mentioned yet. Improbably fighting a Styracosaurus while cranking his neck around at an uncomfortable angle and receiving nasty scratches from the ceratopsian's frilly parts, Cover Rexy is nevertheless notable for his stunningly well-observed, highly birdlike feet. A minor victory for the McLoughlins of the world there, I think, and another one for the collection.

Riley's Deinonychus isn't especially birdlike, with its weedy muscles and slightly shonky head, but the inclusion of such animals in books like this did mark the beginning of a new era in popular depictions of dinosaurs. At least, when they weren't being shoehorned into the old 'reptilian sluggards' mould (which they aren't, in this case). Besides, such agile-looking depictions of smaller dinosaurs lead neatly to...

...Agile-looking depictions of really rather large dinosaurs. I really like this painting - mostly because it's a departure from the otherwise rather static 'great fossil lizards' that inhabit the rest of the book, admittedly, but also because there's a fantastic energy and dynamism about it. It's a worthy stab at depicting Triceratops as an exciting, fearsome animal, and from a tricky perspective, to boot (particularly in an age when multi-angle references weren't so easy to come by). The Battle Damage Frill is a nice touch, too. It may not be perfect, but it demonstrates that Riley could produce an attractive illustration or two, for all his cringeworthy taxonomic mishaps. And I do like to go out on a positive note. You know me...I'm lovely like that.

Next week: an album of teabag freebies!

No comments:

Post a Comment