Time for some more Fornari and Sergio (see also: part 1), and I think it would be pertinent to begin with what seems to be one of the most fondly-remembered illustrations from this book (based on Facebook comments) - an oversized Stegosaurus skeleton, swarming with diminutive museum workers.

It's obvious that the artist never believed that Stegosaurus was really this large - rather, it's a choice made for striking (and quite comic) effect, making liberal use of artistic license. This piece would appear to be one of Sergio's (although, again, no works are individually credited), and indeed the tiny people exhibit the wonderfully individualised and careful touches also seen in his 'sauropods in the city' illustration. The knowing smile of the woman in the foreground hints at the playful nature of this illustration - it's not to be taken too seriously, even if it is quite handy for showing the various techniques used to mount big dinosaur skeletons.

More serious is this illustration, by the same artist, of a dig site. Again, the human figures are wonderful, and it's possible to spend an enjoyable while picking out all the tiny details. However, I'm sure readers of this blog will be with me in their eyes being drawn to the (remarkably complete and articulated) skeleton in the centre, which seems to represent some gigantic new psittacosaurid. It'd probably end up being called Psittacotitan, or Megapsittacosaurus, or something equally lame. Of course, the idea of a gigantic Psittacosaurus-like beast swatting theropods and squishing cheeky mammals to a gooey mush, or maybe just fighting Rodan, is utterly fantastic - so I can hardly blame Sergio for his flight of fancy. In fact, should any readers care to illustrate such a scenario, I'd be more than happy to pack this book off to them. The glorious work of art that makes me laugh the most will surely win. Bonus points for inventing a brilliant scientific binomial for your implausible beast.

I'm pretty sure the 'dig site' painting appeared in Dinosaurs!, but I'm absolutely certain that this slightly off-putting Iguanodon-in-a-sleeping-bag illustration appeared just about everywhere (except Dinosaurs!, oddly enough) back in the '90s. There's something just ever-so-slightly wrong about it, which I'm going to put down to that strange skin texture - it looks more rubbery reptiloid alien than newly-hatched dino-sprog.

The eggy Iguanodon is unmistakably Fornari, and he also provides a number of illustrations of adult Iguanodon, some of which stretch over a number of pages - like this one, which begins on the contents pages, and tails off (hurr) during the foreword. The unusual skin texture reminds me of nothing so much as Normanpedia-era Sibbick, although Niroot has also compared it to Waterhouse Hawkins' Crystal Palace hulks. Beautifully painted, but rather strange. And shouldn't Iguanodon have a beak? The all-round lizardy lips add a touch of the retro.

At least Sergio can be relied upon to provide a much finer, altogether more dinosaurian scaly skin texture, even if his creations are rather derivative. The posture of this Deinonychus is lifted entirely from Bakker's famous illustration, but there's no denying that the carefully shaded skin folds and bulging muscles look fantastic. It has a pleasingly lifelike quality in spite of its scientific obsolescence, which is a significant achievement.

This, on the other hand, is just bloody shameless. Sergio did make the colour scheme considerably nattier, though, so I'll give him that. There's nothing quite like a dandy dinosaur, hence the popularity of illustrations in which monocled theropods where dapper period costume. Speaking of which...

...I am quite in love with this spread, and that's in spite of the fact that the Coelophysis is yet another obvious Sibbick knock-off. When one is required to present dinosaurs alongside human figures for size comparison purposes, why not indulge a little and dress them up in late Victorian outfits? (The humans, that is. Dressing up the saurians would be frowned upon in an educational book, although not by me.) Over on the Facebook page, Niroot dubbed this piece 'The Age of Plateosaurus Innocence,' and the Plateosaurus isn't so bad, even if it is quadrupedal (considered likely at the time) and a little overweight. Of course, I'm really just distracted by that darling hat and the elegance of the parasol. Swoon, etc.

To finish, may I present a particularly indulgent final course in the form of this Late Jurassic panorama by Sergio, featuring any number of both labelled and anonymous contemporaneous creatures. Some of the animals here - like the man-in-suit Ceratosaurus and 'armoured pasty' Stegosaurus - reach near Knightian (as in, Charles R) levels of palaeoart-retro (palaeoretro? Retralaeoart? I should probably stop). Others, like the Allosaurus, I really rather like, even if their heads have been tampered with - it's down to those lovely skin textures again, I think. In fact, the fine line detail evident in this piece is quite something to behold.

On the other side, we have a troop of straw-necked brontosaurs that look uncannily like the Invicta toy - down to the uniform grey colour - and yet another appearance of the 'How literal I am!' bird-grabbing Ornitholestes meme.The tiny add-on hands on the Archaeopteryx are unfortunate, but the feathers are quite lovely, if a little garish. It's always struck me as odd that artists have traditionally seen fit to deck out Archaeopteryx in such a flamboyant fashion. Perhaps it's 'cos scaly reptiles are always really boring shades of Elephantine Grey and Steaming Swampy Brown, while birds are inevitably so fabulously colourful that merely glancing at them induces crippling migraines, hence the need for twitchers to wear those protective visors. Yes, that'll be it.

Next week: something else entirely! But I can't leave Dinosaurs and How They Lived without mentioning that it's been an enjoyable book to review, and there is some quite fantastic artistic talent on show, for all the copycatting. I look forward to despatching it to one of our mad readers.

Showing posts with label the memes!. Show all posts

Showing posts with label the memes!. Show all posts

Tuesday, January 21, 2014

Monday, January 13, 2014

Vintage Dinosaur Art: Dinosaurs and How They Lived

Like so many books of its time, Dinosaurs and How They Lived is an intriguing hodge-podge of the old, the new, and the flagrantly copied. By 1988, the texts of books like these reflected (by and large) post-Dino Renaissance ideas of highly active and evolutionarily successful animals. Outside of top-flight palaeoartist circles, however, the art often leaned on the accomplished, but badly outdated work of '50s-'70s illustrators. And John Sibbick.

Two illustrators are credited for this book - Giuliano Fornari and 'Sergio'. Fornari has illustrated quite a number of dinosaur books aimed at children, and his animals have a very solid, stoic, reptilian look reminiscent of earlier Sibbick (sometimes rather, shall we say, uncannily so...but more on that later). Sergio's approach and style are rather different, and I'd love to know which of the many illustrators named 'Sergio' out there he happens to be. The cover appears to be a Sergio piece (although the book sadly doesn't credit individual works), and depicts some odd-looking dromaeosaurs (tiny hands, lizardy heads and all) hassling what appears to be a Maiasaura. There's much better stuff inside, but at least it's getting the 'dinosaurs were exciting' message across. I guess.

Perhaps the best example of old palaeoart memes meeting new discoveries is this Wealden panorama by Sergio, in which Baryonyx - still the hot new kid on the block at that time - encounters tail-dragging, upright Iguanodon and our old friend, the Tottering Anachronistic Megalosaur (TAM). Happily, the TAM is not only identified as Megalosaurus itself - a legacy of the use of the genus as a taxonomic dumping ground - it also boasts the weird, hunched posture that was obligatory for megalosaurs until the '90s, and probably has its origins in Neave Parker's work. The Iguanodon, for all their outdated tripodal posing, do at least look to be quite normal by contemporary standards. Or...do they?

There's something afoot with these loveable ornithopods. One individual, otherwise quite reminiscent of Sibbick's work in the Normanpedia, seems to have turned to a life of corpse-plundering carnivory. It's all worryingly reminiscent of the cover of Dinosaur Mysteries. Quite what inspired this strange turn isn't clear; there's no mention in the text of possible omnivory, and there are no other instances in the book of herbivores-gone-bad. Perhaps Sergio was just having a bit of fun...

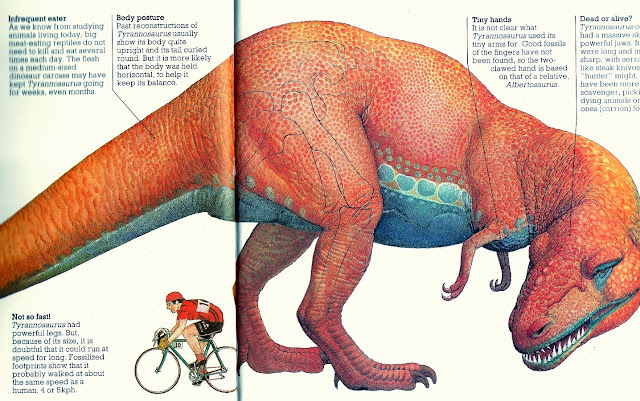

Other Sergio panoramas include this one, showcasing that eternal rivalry. While evidently a proficient artist and illustrator - the fine line work on show is quite lovely - it seems that Sergio didn't really 'do' dinosaurs. The Triceratops look suspiciously Sibbickian, while the T. rex is cribbed from another source entirely. Although I can't for the life of me remember where/whom the original was from, those faithfully reproduced four forward-facing toes are very familiar.

A downside of having multiple illustrators work on a book like this is that the same species can end up looking quite radically different each time it's featured. Here we have Fornari's (I presume) take on T. rex, which is beautifully painted and not too bad for the time, save the rather odd skull, which we can probably put down to a lack of decent 3D references.

Rexy pops up again in a Sergio illustration depicting the groovy psychedelic lightshow of certain death at the end of the Mesozoic. Here, the animal takes on multiple different appearances in the same picture. While perspective problems are afoot, this does seem to be in part due to the different sources used - those in the middleground are based on illustrations by other artists, while the foreground individual is Sergio's take on a Dinamation robot.

What's there left to say about scenes like this? I mean, really. You open up any '80s or '90s kids' dinosaur book, and there's Tenontosaurus shrugging its shoulders as it's shredded to a bloody pulp by a ravening gang of Deinonychus land-piranha. This one (seemingly by Sergio) is quite reminiscent of William Stout's work, with plenty of blood and gore for the kids. Perhaps most striking about this illustration is the depiction of Tenontosaurus, which seems to marry Ely Kish's hauntingly skeletal head with Sibbick's tubbs-o-saurus body. I do appreciate the superb shading on the Deinonychus' meme-tastic neck wattles, though; someone should bring them back (although I guess Luis Rey sorta already did).

Trust 1980s sauropods to show up an illustrator's outdated reference material. Perhaps the worst offender here is the 'Apatosaurus' at right, a true 'brontosaur' complete with mismatched head, blimp-like body and paper-thin neck. (The brachiosaur, meanwhile, reminds me very much of Giovanni Caselli's work.) At the same time, this piece allows us to see the illustrator's true strengths. The background buildings are stunningly, intricately detailed (more than this scan would suggest), while the accompanying birds and pedestrians are invested in plenty of charm and tiny, individual touches - it's a shame I've had to cut most of them out (tiny scanner, see). There ain't no gettin' away from those ugly lardopods, though. Pity.

While the sauropod scene was handled by Sergio, most 'group shots' are illustrated by Fornari. They're quite gorgeous, but to anyone remotely familiar with the Normanpedia, most of them look exceedingly familiar. The Centrosaurus (with its peculiar nose-bulge) and Styracosaurus are near-direct Sibbick copies, while the Chasmosaurus sports an identical colour scheme, even if it's not quite a clone. Skin textures are often quite Sibbickian too, with the occasional sojourn to a finer level of pebbliness. Even if Fornari includes the notable enhancement of a partly-concealed gentleman in dapper costume, such copying deserves a dose of stern finger-wagging.

That said, some of Fornari's Sibbick-tracing can still be appreciated for its unintentionally amusing results. These hadrosaur heads are wonderfully painted, but their resemblance to those placed atop Sibbick's full body versions gives this illustration the air of a grim Mesozoic hunter's lodge. It's as if someone went out a-shootin' those three tonne conifer-munchin' varmints. It's duckbill season!

Next time: more of this sort of thing! There are a few fondly remembered illustrations in this book, mostly of skeletons, that I'd never be forgiven for not featuring. And so I will. Don't say I don't do you any favours.

Two illustrators are credited for this book - Giuliano Fornari and 'Sergio'. Fornari has illustrated quite a number of dinosaur books aimed at children, and his animals have a very solid, stoic, reptilian look reminiscent of earlier Sibbick (sometimes rather, shall we say, uncannily so...but more on that later). Sergio's approach and style are rather different, and I'd love to know which of the many illustrators named 'Sergio' out there he happens to be. The cover appears to be a Sergio piece (although the book sadly doesn't credit individual works), and depicts some odd-looking dromaeosaurs (tiny hands, lizardy heads and all) hassling what appears to be a Maiasaura. There's much better stuff inside, but at least it's getting the 'dinosaurs were exciting' message across. I guess.

Perhaps the best example of old palaeoart memes meeting new discoveries is this Wealden panorama by Sergio, in which Baryonyx - still the hot new kid on the block at that time - encounters tail-dragging, upright Iguanodon and our old friend, the Tottering Anachronistic Megalosaur (TAM). Happily, the TAM is not only identified as Megalosaurus itself - a legacy of the use of the genus as a taxonomic dumping ground - it also boasts the weird, hunched posture that was obligatory for megalosaurs until the '90s, and probably has its origins in Neave Parker's work. The Iguanodon, for all their outdated tripodal posing, do at least look to be quite normal by contemporary standards. Or...do they?

There's something afoot with these loveable ornithopods. One individual, otherwise quite reminiscent of Sibbick's work in the Normanpedia, seems to have turned to a life of corpse-plundering carnivory. It's all worryingly reminiscent of the cover of Dinosaur Mysteries. Quite what inspired this strange turn isn't clear; there's no mention in the text of possible omnivory, and there are no other instances in the book of herbivores-gone-bad. Perhaps Sergio was just having a bit of fun...

Other Sergio panoramas include this one, showcasing that eternal rivalry. While evidently a proficient artist and illustrator - the fine line work on show is quite lovely - it seems that Sergio didn't really 'do' dinosaurs. The Triceratops look suspiciously Sibbickian, while the T. rex is cribbed from another source entirely. Although I can't for the life of me remember where/whom the original was from, those faithfully reproduced four forward-facing toes are very familiar.

A downside of having multiple illustrators work on a book like this is that the same species can end up looking quite radically different each time it's featured. Here we have Fornari's (I presume) take on T. rex, which is beautifully painted and not too bad for the time, save the rather odd skull, which we can probably put down to a lack of decent 3D references.

Rexy pops up again in a Sergio illustration depicting the groovy psychedelic lightshow of certain death at the end of the Mesozoic. Here, the animal takes on multiple different appearances in the same picture. While perspective problems are afoot, this does seem to be in part due to the different sources used - those in the middleground are based on illustrations by other artists, while the foreground individual is Sergio's take on a Dinamation robot.

What's there left to say about scenes like this? I mean, really. You open up any '80s or '90s kids' dinosaur book, and there's Tenontosaurus shrugging its shoulders as it's shredded to a bloody pulp by a ravening gang of Deinonychus land-piranha. This one (seemingly by Sergio) is quite reminiscent of William Stout's work, with plenty of blood and gore for the kids. Perhaps most striking about this illustration is the depiction of Tenontosaurus, which seems to marry Ely Kish's hauntingly skeletal head with Sibbick's tubbs-o-saurus body. I do appreciate the superb shading on the Deinonychus' meme-tastic neck wattles, though; someone should bring them back (although I guess Luis Rey sorta already did).

Trust 1980s sauropods to show up an illustrator's outdated reference material. Perhaps the worst offender here is the 'Apatosaurus' at right, a true 'brontosaur' complete with mismatched head, blimp-like body and paper-thin neck. (The brachiosaur, meanwhile, reminds me very much of Giovanni Caselli's work.) At the same time, this piece allows us to see the illustrator's true strengths. The background buildings are stunningly, intricately detailed (more than this scan would suggest), while the accompanying birds and pedestrians are invested in plenty of charm and tiny, individual touches - it's a shame I've had to cut most of them out (tiny scanner, see). There ain't no gettin' away from those ugly lardopods, though. Pity.

While the sauropod scene was handled by Sergio, most 'group shots' are illustrated by Fornari. They're quite gorgeous, but to anyone remotely familiar with the Normanpedia, most of them look exceedingly familiar. The Centrosaurus (with its peculiar nose-bulge) and Styracosaurus are near-direct Sibbick copies, while the Chasmosaurus sports an identical colour scheme, even if it's not quite a clone. Skin textures are often quite Sibbickian too, with the occasional sojourn to a finer level of pebbliness. Even if Fornari includes the notable enhancement of a partly-concealed gentleman in dapper costume, such copying deserves a dose of stern finger-wagging.

That said, some of Fornari's Sibbick-tracing can still be appreciated for its unintentionally amusing results. These hadrosaur heads are wonderfully painted, but their resemblance to those placed atop Sibbick's full body versions gives this illustration the air of a grim Mesozoic hunter's lodge. It's as if someone went out a-shootin' those three tonne conifer-munchin' varmints. It's duckbill season!

Next time: more of this sort of thing! There are a few fondly remembered illustrations in this book, mostly of skeletons, that I'd never be forgiven for not featuring. And so I will. Don't say I don't do you any favours.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)