Perhaps most prominent among the illustrators for this book - if for no other reason than his work appears on the cover (at least, of the edition I have) - is Michael Rothman. Rothman's work is quite vibrant, with an emphasis on lush greenery that lends his best pieces a quite naturalistic feel. In fact, his plants and landscapes are frequently better than his dinosaurs, which are afflicted by a few contemporaneous palaeoart tropes. But more on that shortly.

|

| With apologies for the dreadful scan. |

In addition to a certain painterly (shot!) loveliness, Rothman's work also quite clearly exhibits influences from the most prominent palaeoartists of the period, including John Gurche and Mark Hallett. This is nowhere more evident than in the skin textures of the animals he paints; they have a certain leatheriness that seems evocative of Gurche in particular. While the above illustration appears to be an attempt to cram absolutely every early '90s palaeoart trope into one image (naked dromaeosaurs being badasseses! Motherly ornithopods! Noodle-necked elephantine-skinned brachiosaurs! Big armed ol' T. rex with Hallett-o-horns!), it's likely to be a deliberate 'montage' of different animals. In the book, it precedes a chapter that takes a look at the diversity of dinosaurs (andotherancientcreatures). All the same, it's a fun encapsulation of early '90s attitudes - the rather Gurche-esque dromaeosaur in particular. Spot what appears to be a sauropod looking back over its shoulder in the top left - like a less barmy version of the Invicta Mamenchisaurus.

Rothman's cover illustrations are also featured inside the book at a larger size, all the better for a more thorough appreciation. His rather sad and melty-looking brown Apatosaurus reminds me a great deal of Sibbick's work, although that's probably because that's what I grew up with - Sibbick himself borrowed from Hallett back in the '80s. The rather emaciated - dessicated, even - head contrasts with the more rotund (although not overly so) body, while the neck lacks that characteristic apatosaurian extreme width. In fact, it almost seems to become a ribbon at one point. While serviceable as an illustration of a brown sauropod for a museum dinosaur book, this is perhaps the best example of where Rothman's skill at depicting flora comes to the fore. There's a pleasing realism to the splintered pines, and he puts them to good use in the composition. One should never underestimate how much decent scenery adds to the believability of palaeoart.

The power of a well-painted backdrop is nowhere more evident that in both the theatre, and in depictions of Triceratops totally bloodily goring Tyrannosaurus just below the knee. This gently sloping forestscape is just wonderful, although the positioning of the animals here is a little peculiar - like Rexy was just minding his own business, taking a stroll through the forest, when a mad Triceratops barged its way through and slashed his knee. The restoration of the animals isn't too shabby for the time, although Rexy's (again) rather oversized arms are curious, and the splayed hand pointing directly at the viewer reminds me of nothing so much as a certain famous First World War propaganda sheet (American readers might be more familiar with an Uncle Sam-featuring copycat).

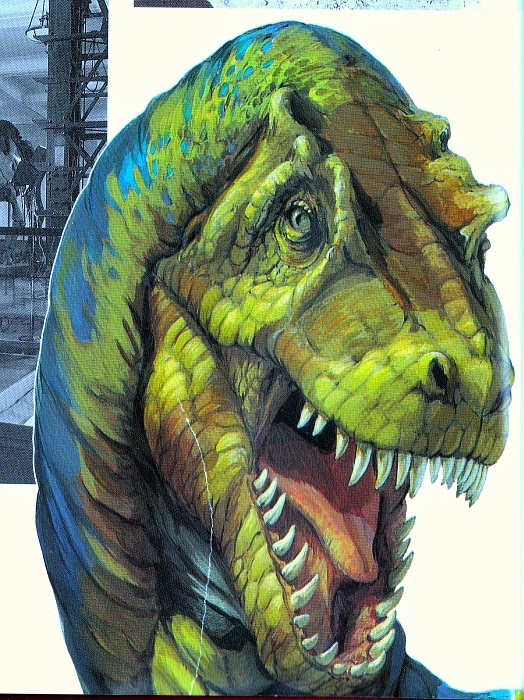

A few of Rothman's dinosaurs appear shorn of backgrounds, and they don't hold up nearly as well today. This slightly Stoutian Rexy isn't the worst ever, but is inferior to the one featured in the scene with Triceratops; it suffers from a slightly disproportionate and bony fizzog with enormous, plate-like scales. (Is it just me, or is that a rather coy expression? You alarming devil, Sexy Rexy, you.)

Rothman provides further 'profile' or 'diagnostic' illustrations for the book's 'Gallery of Dinosaurs' (andotherancientcreatures). Contrary to his crocodilian-faced Rexy, they often appear to be largely devoid of dinosaurian scales, instead sporting highly wrinkled, leathery skin. By and large, they are very reminiscent of Sibbick's work for the Normanpedia, although the animals are a little less shapeless in appearance. When compared with Sibbick's lumbering giant theropods, Rothman's Albertosaurus (above) appears very sprightly and agile.

Perhaps most Sibbickesque in appearance is Rothman's Edmontosaurus (in style only; it's not a copy of Sibbick's). Or at least, its back end is - the vintage Sibbick-style Michelin Man skin texture blends into finer scales towards the frond of the animal. Although dated now, there is a pleasing chunky solidity to it - even devoid of context, the creature appears physically massive and heavy, without being overly bloated.

But what of the other artists? Well, I'm happy to report that James Robins has a decent amount of work featured in this book, which I might just have to feature in a post all on its own. His clean, unfussy, and highly modern style contrasts markedly with Rothman's more traditional approach while, as ever, his Paulian maniraptors look as startlingly 'plucked' as they should. His Oviraptor (above) is superb for its time, but Robins' depictions of this dinosaur would become still more prescient in the immediately following years...even if they remained featherless.

And speaking of feathers...unusually, Archaeopteryx is not alone in sporting full-on birdy plumage in the AMNH book - Mononykus does too! Ah, but that's only because it was believed by some authorities at the time to have definitively been a bird (as in, an avialan bird) - not least co-describer Mark Norrell, who in the AMNH book describes how he and his colleagues initially believed the animal to be a non-avian dinosaur, before realising that they'd 'dug up a bird'. As a result, Mononykus is one of the few non-avian theropods discovered prior to 1996 that it's difficult to find an unfeathered illustration of (alongside Avimimus).* The book's illustration (above) - by, you guessed it, Rothman - is quite a treat, and in many respects ahead of its time in depicting a non-avian theropod with such advanced, complex feathers...even if they did think it was a 'proper' bird back then. (Whatever that even means anymore.) It's a lovely piece, with the lighting on the animal's fluffy feather coat being particularly noteworthy. Arguably, it also avoids making the animal look like some sort of monstrous 'lizard-bird', instead presenting a creature that seems of a piece - more than a lot of artists can manage today. A lesson in painting feathered dinosaurs from 1993 - not what I was expecting when I first opened this book!

*Oh, but I did find one. Thank you, Google image search.

No comments:

Post a Comment