Over the years of writing these blog posts, I'd like to think that I've matured somewhat - that the vodka-fuelled gratuity of my late university years has mellowed into something more thoughtful and, dare I say it, nuanced. (Oh yes. I went there.) Sure, I'll still point out shonky dinosaur art, but with less savagery, and an acknowledgement that, by contemporary standards, it's often not so bad. Plus, illustrators gotta eat.

On the other hand, one is occasionally reminded that a few - a very few - palaeoartists over the years managed to make their jobbing contemporaries' work look more than a little embarrassing - maybe, even, deserving of the occasional pouring of scorn. One of those artists is James Robins.

While we've looked at Robins' work here before, I think it's always worth revisiting him. As an illustrator of dinosaur books, Robins often gets overlooked historically in favour of palaeoart's Big Names. This is a pity, because Robins' work was often well ahead of the curve, especially in the early '90s. The worst palaeoart tropes of the previous decades were on the way out, but still lingered in every tail-dragging, rotund sauropod, freakish, dainty-handed dromaeosaur, and nonspecific tyrannosaur with zipper teeth. Robins' work stands out because, damn it, he actually paid attention to anatomical references. His highly precise approach contrasts sharply with Rothman's rather more, er, old-fashioned style - it might not quite be Ankylosaurus by modern standards, but that's still a pretty stylish-looking beast (above).

His Tenontosaurus, too, is far sleeker and more sprightly-looking than early '90s audiences were probably used to, especially since Sibbick's '80s version (from his endlessly copied illustrations for the Normanpedia) was far weightier and stodgier-looking, dragged tail and all. It also appears devoid of dromaeosaur hitchhikers...which is nice. The goat-like pupils are another neat touch, and harken back to the work of John McLoughlin.

If there's one unfortunate aspect of Robins' work for the AMNH book, it's that it's - typically for him - confined to 'spotter's guide'-type illustrations of animals against plain white backgrounds. Robins is perfectly capable of painting landscapes, but it seems that he was more often commissioned to produce this more diagrammatical work. But I'm grateful for what I can get. Robins' Protoceratops (above) is remarkable for the early '90s, an age when the animal tended to be stuck in a semi-sprawling 1970s timewarp.

Sadly, there aren't too many Robins theropods in the AMNH book; in addition to the excellent Oviraptor featured in the last post, we're also given this Coelophysis pair. Again, it's commendable for its fine details (down to the vestigial fingers) and overall modern look. Coelophysis often didn't fare too well in the early '90s - I'm still haunted by the freakish illustrations that appeared in Dinosaurs! The Jurassic Park toys were cool, though. Pipe-cleaner-o-saurus!

To compensate for the lack of theropods, we are granted an unusually diverse selection of Robins non-dinosaurs. For starters, here's the gharial-like phytosaur Rutiodon decked out in a very fetching stripy brick red colour scheme...

...Followed by the ichthyosaur Stenopterygius, famous for carelessly allowing its very new-not-quite-born babies to become hopelessly killed and fossilised. While not terribly exciting, it's a pleasing enough piece; Robins' penchant for fine line work is put to good effect. I like the red eye, too. It falls on the right side of the 'striking and reptilian/Halloween monster' divide.

His Eurhinodelphis is more monstrous-looking, but it's not Robins' fault - the creature really did have a nose like that. Ridiculous. That dappled light is quite lovely, though. Noteworthy here is the speculative incipient dorsal fin, which Robins illustrates with a rather unusual 'plateau' shape.

But never mind all that - how many readers had no idea that Robins did prehistoric mammals? Me too! It's always a pleasant surprise to learn that an artist's prehistoric animal repertoire is wider than you imagined. Quite few people seem to realise that, for example, Luis Rey does prehistoric mammals, too - and rather well. (And no, they're not brightly coloured).

And with that...ancient alpacas! Now there's a series for you, History Channel. Alien camelids descending on the earliest human civilisations, helping them construct the pyramids, the great Aztec cities, Atlantis, etc. etc., before getting grumpy, spitting at the poxy monkeys and zipping back off into space? Fantastic. It would also explain how camelids had such a significant role in the development of advanced civilisations in both Africa and the Americas (because they did, you know) THINK ABOUT IT.

What I meant to say was: here's Robins' illustration of the early camelid Stenomylus. It's an animal that seldom appears in popular dinosaur andotherprehistoricanimal books, perhaps due to its lack of large teeth, claws, size, or other sexy attributes. It was a wee camelid that lived in North America, lacked some features of modern camelids, and that's about it. But hey, Robins does a nice job - love those stripy pelts and (at the risk of flogging a dead camelid) superb small details. Stenomylus - and Robins - take a bow.

Next week - Doctor Who! No, not Peter Capaldi (well, maybe Peter Capaldi), but a 1976 book featuring dinosaurs and occasionally uncanny depictions of Tom Baker. I can't wait to share it.

Tuesday, August 19, 2014

Monday, August 11, 2014

Bront�saurus?

|

| Bront�saurus?. Sepia ink and gouache on Strathmore grey toned paper, 151 x 147mm. |

'My literary and palaeo friends and audiences so rarely converge (which is a great pity), but I�m jolly well going to try.'

So I said when I first shared this drawing on my own illustration blog, Twitter, and Facebook page a few weeks ago. It has since gained what was for me quite unprecedented attention for a single piece of work on any of those media platforms.* Why, it's even been spread about on Tumblr without any attribution, which I daresay is about as 'viral' as it gets for me. As usual, I hesitated sharing it here from the first because it offers very little next to the nutritional goodness posted by my Chasmosaurs brethren, but I've been persuaded otherwise. Stay tuned, therefore, for more in this series.

*Except perhaps for Ol' Salty, which was shared by the Stan Winston School of Character Arts' Facebook page, though as they uploaded the drawing afresh instead of sharing it directly from mine, the figures were not reflected in the latter. *Chagrined mutterings*

Wednesday, August 6, 2014

Vintage Dinosaur Art: The American Museum of Natural History's Book of Dinosaurs

Meeting our Vintage Dinosaur Art criterion by the slimmest of margins, The American Museum of Natural History's Book of Dinosaurs and Other Ancient Creatures (snappier titles are there none) is a mere twenty years old. However - and as I've said numerous times before - it's amazing how much has changed since the early '90s, even when it comes to restorations of dinosaurs that aren't (yet) known to have been feathered. The AMNH book (as I'm sure you won't mind me calling it) is also notable for featuring artists with differing approaches and styles, which only adds further historical interest. Some of our old friends are in there, but there's at least one highly notable contributor who hasn't been featured in a VDA post before...which always makes me So Very Happy.

Perhaps most prominent among the illustrators for this book - if for no other reason than his work appears on the cover (at least, of the edition I have) - is Michael Rothman. Rothman's work is quite vibrant, with an emphasis on lush greenery that lends his best pieces a quite naturalistic feel. In fact, his plants and landscapes are frequently better than his dinosaurs, which are afflicted by a few contemporaneous palaeoart tropes. But more on that shortly.

Rothman's style also occasionally gives his paintings the air of much earlier, Burian-era palaeoart, which I certainly don't object to. There's something rather stately and solid about them, and this particularly applies to the above sepia-tinged scene, in which a brachiosaur adult and juvenile are harassed by a gang of allosaurs, while other Late Jurassic denizens look on. Such are the changing trends even in the artistic styles of palaeoart - never mind the depiction of the animals themselves - that this piece looks much older than it really is at first glance, and it takes the relatively svelte animals to remind us that we're looking at a post-Dino Renaissance work. Of course, there's much that's still just Plain Retro from our standpoint. Perhaps most notably, there's that manifestation of the peculiar notion that sauropod necks were like squishy octopus tentacles with a perma-grinning mug glued to one end. Bones? Where we're going, we won't need bones!

In addition to a certain painterly (shot!) loveliness, Rothman's work also quite clearly exhibits influences from the most prominent palaeoartists of the period, including John Gurche and Mark Hallett. This is nowhere more evident than in the skin textures of the animals he paints; they have a certain leatheriness that seems evocative of Gurche in particular. While the above illustration appears to be an attempt to cram absolutely every early '90s palaeoart trope into one image (naked dromaeosaurs being badasseses! Motherly ornithopods! Noodle-necked elephantine-skinned brachiosaurs! Big armed ol' T. rex with Hallett-o-horns!), it's likely to be a deliberate 'montage' of different animals. In the book, it precedes a chapter that takes a look at the diversity of dinosaurs (andotherancientcreatures). All the same, it's a fun encapsulation of early '90s attitudes - the rather Gurche-esque dromaeosaur in particular. Spot what appears to be a sauropod looking back over its shoulder in the top left - like a less barmy version of the Invicta Mamenchisaurus.

Rothman's cover illustrations are also featured inside the book at a larger size, all the better for a more thorough appreciation. His rather sad and melty-looking brown Apatosaurus reminds me a great deal of Sibbick's work, although that's probably because that's what I grew up with - Sibbick himself borrowed from Hallett back in the '80s. The rather emaciated - dessicated, even - head contrasts with the more rotund (although not overly so) body, while the neck lacks that characteristic apatosaurian extreme width. In fact, it almost seems to become a ribbon at one point. While serviceable as an illustration of a brown sauropod for a museum dinosaur book, this is perhaps the best example of where Rothman's skill at depicting flora comes to the fore. There's a pleasing realism to the splintered pines, and he puts them to good use in the composition. One should never underestimate how much decent scenery adds to the believability of palaeoart.

The power of a well-painted backdrop is nowhere more evident that in both the theatre, and in depictions of Triceratops totally bloodily goring Tyrannosaurus just below the knee. This gently sloping forestscape is just wonderful, although the positioning of the animals here is a little peculiar - like Rexy was just minding his own business, taking a stroll through the forest, when a mad Triceratops barged its way through and slashed his knee. The restoration of the animals isn't too shabby for the time, although Rexy's (again) rather oversized arms are curious, and the splayed hand pointing directly at the viewer reminds me of nothing so much as a certain famous First World War propaganda sheet (American readers might be more familiar with an Uncle Sam-featuring copycat).

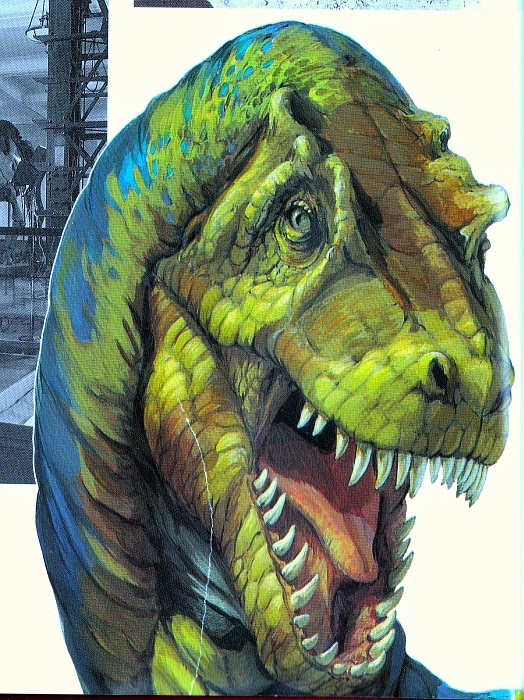

A few of Rothman's dinosaurs appear shorn of backgrounds, and they don't hold up nearly as well today. This slightly Stoutian Rexy isn't the worst ever, but is inferior to the one featured in the scene with Triceratops; it suffers from a slightly disproportionate and bony fizzog with enormous, plate-like scales. (Is it just me, or is that a rather coy expression? You alarming devil, Sexy Rexy, you.)

Rothman provides further 'profile' or 'diagnostic' illustrations for the book's 'Gallery of Dinosaurs' (andotherancientcreatures). Contrary to his crocodilian-faced Rexy, they often appear to be largely devoid of dinosaurian scales, instead sporting highly wrinkled, leathery skin. By and large, they are very reminiscent of Sibbick's work for the Normanpedia, although the animals are a little less shapeless in appearance. When compared with Sibbick's lumbering giant theropods, Rothman's Albertosaurus (above) appears very sprightly and agile.

Perhaps most Sibbickesque in appearance is Rothman's Edmontosaurus (in style only; it's not a copy of Sibbick's). Or at least, its back end is - the vintage Sibbick-style Michelin Man skin texture blends into finer scales towards the frond of the animal. Although dated now, there is a pleasing chunky solidity to it - even devoid of context, the creature appears physically massive and heavy, without being overly bloated.

But what of the other artists? Well, I'm happy to report that James Robins has a decent amount of work featured in this book, which I might just have to feature in a post all on its own. His clean, unfussy, and highly modern style contrasts markedly with Rothman's more traditional approach while, as ever, his Paulian maniraptors look as startlingly 'plucked' as they should. His Oviraptor (above) is superb for its time, but Robins' depictions of this dinosaur would become still more prescient in the immediately following years...even if they remained featherless.

And speaking of feathers...unusually, Archaeopteryx is not alone in sporting full-on birdy plumage in the AMNH book - Mononykus does too! Ah, but that's only because it was believed by some authorities at the time to have definitively been a bird (as in, an avialan bird) - not least co-describer Mark Norrell, who in the AMNH book describes how he and his colleagues initially believed the animal to be a non-avian dinosaur, before realising that they'd 'dug up a bird'. As a result, Mononykus is one of the few non-avian theropods discovered prior to 1996 that it's difficult to find an unfeathered illustration of (alongside Avimimus).* The book's illustration (above) - by, you guessed it, Rothman - is quite a treat, and in many respects ahead of its time in depicting a non-avian theropod with such advanced, complex feathers...even if they did think it was a 'proper' bird back then. (Whatever that even means anymore.) It's a lovely piece, with the lighting on the animal's fluffy feather coat being particularly noteworthy. Arguably, it also avoids making the animal look like some sort of monstrous 'lizard-bird', instead presenting a creature that seems of a piece - more than a lot of artists can manage today. A lesson in painting feathered dinosaurs from 1993 - not what I was expecting when I first opened this book!

*Oh, but I did find one. Thank you, Google image search.

Perhaps most prominent among the illustrators for this book - if for no other reason than his work appears on the cover (at least, of the edition I have) - is Michael Rothman. Rothman's work is quite vibrant, with an emphasis on lush greenery that lends his best pieces a quite naturalistic feel. In fact, his plants and landscapes are frequently better than his dinosaurs, which are afflicted by a few contemporaneous palaeoart tropes. But more on that shortly.

|

| With apologies for the dreadful scan. |

In addition to a certain painterly (shot!) loveliness, Rothman's work also quite clearly exhibits influences from the most prominent palaeoartists of the period, including John Gurche and Mark Hallett. This is nowhere more evident than in the skin textures of the animals he paints; they have a certain leatheriness that seems evocative of Gurche in particular. While the above illustration appears to be an attempt to cram absolutely every early '90s palaeoart trope into one image (naked dromaeosaurs being badasseses! Motherly ornithopods! Noodle-necked elephantine-skinned brachiosaurs! Big armed ol' T. rex with Hallett-o-horns!), it's likely to be a deliberate 'montage' of different animals. In the book, it precedes a chapter that takes a look at the diversity of dinosaurs (andotherancientcreatures). All the same, it's a fun encapsulation of early '90s attitudes - the rather Gurche-esque dromaeosaur in particular. Spot what appears to be a sauropod looking back over its shoulder in the top left - like a less barmy version of the Invicta Mamenchisaurus.

Rothman's cover illustrations are also featured inside the book at a larger size, all the better for a more thorough appreciation. His rather sad and melty-looking brown Apatosaurus reminds me a great deal of Sibbick's work, although that's probably because that's what I grew up with - Sibbick himself borrowed from Hallett back in the '80s. The rather emaciated - dessicated, even - head contrasts with the more rotund (although not overly so) body, while the neck lacks that characteristic apatosaurian extreme width. In fact, it almost seems to become a ribbon at one point. While serviceable as an illustration of a brown sauropod for a museum dinosaur book, this is perhaps the best example of where Rothman's skill at depicting flora comes to the fore. There's a pleasing realism to the splintered pines, and he puts them to good use in the composition. One should never underestimate how much decent scenery adds to the believability of palaeoart.

The power of a well-painted backdrop is nowhere more evident that in both the theatre, and in depictions of Triceratops totally bloodily goring Tyrannosaurus just below the knee. This gently sloping forestscape is just wonderful, although the positioning of the animals here is a little peculiar - like Rexy was just minding his own business, taking a stroll through the forest, when a mad Triceratops barged its way through and slashed his knee. The restoration of the animals isn't too shabby for the time, although Rexy's (again) rather oversized arms are curious, and the splayed hand pointing directly at the viewer reminds me of nothing so much as a certain famous First World War propaganda sheet (American readers might be more familiar with an Uncle Sam-featuring copycat).

A few of Rothman's dinosaurs appear shorn of backgrounds, and they don't hold up nearly as well today. This slightly Stoutian Rexy isn't the worst ever, but is inferior to the one featured in the scene with Triceratops; it suffers from a slightly disproportionate and bony fizzog with enormous, plate-like scales. (Is it just me, or is that a rather coy expression? You alarming devil, Sexy Rexy, you.)

Rothman provides further 'profile' or 'diagnostic' illustrations for the book's 'Gallery of Dinosaurs' (andotherancientcreatures). Contrary to his crocodilian-faced Rexy, they often appear to be largely devoid of dinosaurian scales, instead sporting highly wrinkled, leathery skin. By and large, they are very reminiscent of Sibbick's work for the Normanpedia, although the animals are a little less shapeless in appearance. When compared with Sibbick's lumbering giant theropods, Rothman's Albertosaurus (above) appears very sprightly and agile.

Perhaps most Sibbickesque in appearance is Rothman's Edmontosaurus (in style only; it's not a copy of Sibbick's). Or at least, its back end is - the vintage Sibbick-style Michelin Man skin texture blends into finer scales towards the frond of the animal. Although dated now, there is a pleasing chunky solidity to it - even devoid of context, the creature appears physically massive and heavy, without being overly bloated.

But what of the other artists? Well, I'm happy to report that James Robins has a decent amount of work featured in this book, which I might just have to feature in a post all on its own. His clean, unfussy, and highly modern style contrasts markedly with Rothman's more traditional approach while, as ever, his Paulian maniraptors look as startlingly 'plucked' as they should. His Oviraptor (above) is superb for its time, but Robins' depictions of this dinosaur would become still more prescient in the immediately following years...even if they remained featherless.

And speaking of feathers...unusually, Archaeopteryx is not alone in sporting full-on birdy plumage in the AMNH book - Mononykus does too! Ah, but that's only because it was believed by some authorities at the time to have definitively been a bird (as in, an avialan bird) - not least co-describer Mark Norrell, who in the AMNH book describes how he and his colleagues initially believed the animal to be a non-avian dinosaur, before realising that they'd 'dug up a bird'. As a result, Mononykus is one of the few non-avian theropods discovered prior to 1996 that it's difficult to find an unfeathered illustration of (alongside Avimimus).* The book's illustration (above) - by, you guessed it, Rothman - is quite a treat, and in many respects ahead of its time in depicting a non-avian theropod with such advanced, complex feathers...even if they did think it was a 'proper' bird back then. (Whatever that even means anymore.) It's a lovely piece, with the lighting on the animal's fluffy feather coat being particularly noteworthy. Arguably, it also avoids making the animal look like some sort of monstrous 'lizard-bird', instead presenting a creature that seems of a piece - more than a lot of artists can manage today. A lesson in painting feathered dinosaurs from 1993 - not what I was expecting when I first opened this book!

*Oh, but I did find one. Thank you, Google image search.

Friday, July 25, 2014

Interview: Sophie Campbell

We here at LITC were pleasantly surprised by Sophie Campbell's art in the recent Turtles in Time #1, which depicted all of its prehistoric creatures with various feathery coverings (including, presciently enough, the ornithischians.) When it turned out that Sophie Campbell is active on Deviantart, well, that was too tempting an opportunity to resist. I reached out with a few questions, and she was kind of enough to reply.

So how did you end up on the Turtles in Time creative team? Did you have much input on the setting and on which dinosaurs were featured?

My editor Bobby asked if I wanted to draw Turtles in Time #1, I said "of course I do," and that was that! The writer, Paul Allor, and I talked a bit beforehand about the setting and which dinosaurs we were going to use. Paul picked the ones neccessary for his script, though, such as the Tyrannosaurus and the Triceratops, although for some of them it was more of a general type, like something that could fly. The specific species was left to me.

Since my mom saves everything, I pulled out a bunch of old dinosaur books I had as a kid and picked out the ones I liked and which fit the time period and setting. I picked all of the background dinosaurs myself, such as the Therizinosaurus and Pepperoni [the baby Protoceratops Raphael takes as a pet]. When I came on board, I was determined to give the Turtles an adorable dinosaur sidekick, and I wouldn't rest until I'd gotten her into the story! For the flying reptile we needed Mikey to ride, I decided on the Quetzalcoatlus, not just because of the time period but because it seemed the most rid-

able.

Pepperoni is a great little side character. Do you have much of an interest in paleontology? Do you see yourself drawing them again in the future?

I don't have a big, active interest in it, other then that I like dinosaurs. I don't read up on the science or the new discoveries that often, but I still enjoy it. I especially love reading about the weird discoveries that shatter the popular image of what people think dinosaurs are. I used to draw dinosaurs a lot as a kid, and I'd love to draw them again in the future. I'm doing a Ninja-Turtles fan-comic right now that I post online, and some dinosaurs might show up in that.

What was the process you used to do the dinosaur character design? Was it something you had a lot of freedom with?

Paul and I were on the same page before we ever discussed it. I've always loved dinosaurs with feathers since I was a kid, so I knew that was what I was going to do. I wasn't sure how Paul or Nickelodeon would like it, although I was prepared to fight for it. I can get pretty stubborn. But luckily, Paul asked for feathered dinosaurs before I even said anything, so it worked out. Early on I had been planning on coloring the issue myself, so when I did dinosaur sketches I did color schemes for them too. Some of which eventual colorist Bill Crabtree used, like the colors for the Tyrannosaurus and Pepperoni. Nickelodeon didn't like my Triceratops colors, so we had to change that. It was a little too weird, I guess.

I love bright and weird colored dinosaurs, though. I get bored of everything always being shown in grey and brown and single solid colors. I wanted the dinosaurs in the background to be more colorful than they ended up being, but there was a bit of concern over my Valentine's Day/Easter-colored dinosaurs, so it was scaled back.

Another thing was that even though I wanted there to be some accuracy, like the feathers, I also wanted it to be cartoony and cute. I love Jurassic Park and all that, but I get a little tired of dinosaurs always being expected to be "badass" and fearsome and ugly all of the time. So I wanted to do something in the middle, which, to me anyway, makes them seem more believable within the world of the comic. And it just fit the tone better.

Was there any kind of dinosaur that you wanted to add but couldn't?

I would have liked to have drawn some swimming dinosaurs, and it would have been fun to draw the Turtles dealing with something really big, like a Mamenchiasaurus. It would be fun to draw something at that scale.

Finally, what's your favorite prehistoric animal?

I love Glyptodon! And Deinonychus.

Thanks for the interview! OK, Pepperoni, play us out.

So how did you end up on the Turtles in Time creative team? Did you have much input on the setting and on which dinosaurs were featured?

My editor Bobby asked if I wanted to draw Turtles in Time #1, I said "of course I do," and that was that! The writer, Paul Allor, and I talked a bit beforehand about the setting and which dinosaurs we were going to use. Paul picked the ones neccessary for his script, though, such as the Tyrannosaurus and the Triceratops, although for some of them it was more of a general type, like something that could fly. The specific species was left to me.

Since my mom saves everything, I pulled out a bunch of old dinosaur books I had as a kid and picked out the ones I liked and which fit the time period and setting. I picked all of the background dinosaurs myself, such as the Therizinosaurus and Pepperoni [the baby Protoceratops Raphael takes as a pet]. When I came on board, I was determined to give the Turtles an adorable dinosaur sidekick, and I wouldn't rest until I'd gotten her into the story! For the flying reptile we needed Mikey to ride, I decided on the Quetzalcoatlus, not just because of the time period but because it seemed the most rid-

able.

Pepperoni is a great little side character. Do you have much of an interest in paleontology? Do you see yourself drawing them again in the future?

I don't have a big, active interest in it, other then that I like dinosaurs. I don't read up on the science or the new discoveries that often, but I still enjoy it. I especially love reading about the weird discoveries that shatter the popular image of what people think dinosaurs are. I used to draw dinosaurs a lot as a kid, and I'd love to draw them again in the future. I'm doing a Ninja-Turtles fan-comic right now that I post online, and some dinosaurs might show up in that.

|

|

What was the process you used to do the dinosaur character design? Was it something you had a lot of freedom with?

Paul and I were on the same page before we ever discussed it. I've always loved dinosaurs with feathers since I was a kid, so I knew that was what I was going to do. I wasn't sure how Paul or Nickelodeon would like it, although I was prepared to fight for it. I can get pretty stubborn. But luckily, Paul asked for feathered dinosaurs before I even said anything, so it worked out. Early on I had been planning on coloring the issue myself, so when I did dinosaur sketches I did color schemes for them too. Some of which eventual colorist Bill Crabtree used, like the colors for the Tyrannosaurus and Pepperoni. Nickelodeon didn't like my Triceratops colors, so we had to change that. It was a little too weird, I guess.

|

Another thing was that even though I wanted there to be some accuracy, like the feathers, I also wanted it to be cartoony and cute. I love Jurassic Park and all that, but I get a little tired of dinosaurs always being expected to be "badass" and fearsome and ugly all of the time. So I wanted to do something in the middle, which, to me anyway, makes them seem more believable within the world of the comic. And it just fit the tone better.

Was there any kind of dinosaur that you wanted to add but couldn't?

I would have liked to have drawn some swimming dinosaurs, and it would have been fun to draw the Turtles dealing with something really big, like a Mamenchiasaurus. It would be fun to draw something at that scale.

Finally, what's your favorite prehistoric animal?

I love Glyptodon! And Deinonychus.

Thanks for the interview! OK, Pepperoni, play us out.

Subsequent to the publication of this article, the artist came out as a trans woman. This post has been edited to reflect her name change.

Tuesday, July 22, 2014

Vintage Dinosaur Art: The Mysterious World of Dinosaurs - Part 2

In the first part of our examination of The Mysterious World of Dinosaurs, we came upon chubby, oily-looking tyrannosaurs, alarmingly carnivorous-looking stegosaurs, and Godzilla. However - and as the title implies - this book goes beyond the eponymous archosaur clade, taking a look at various other Mesozoic monstrosities. Bring on the zombie-pterosaurs!

Now let's be fair - depicting pterosaurs in dessicated, mummy-like fashion was commonplace at the time this book was produced. Contemporary mass estimates had giants like Pteranodon weigh about the same as the shrivelled walnut that sits between Ken Ham's ears. In order to make sense of this, life restorations had to be stripped of all but the most essential bodily tissues, and occasionally even of those. Phillipps' Pterodactylus (above) is not an aberration, but the norm - right down to the erroneous dangling bat-posture. As it happens, I believe this is a rather effective plate - it's striking, nicely composed, and shows the animal's key attributes and overall form rather nicely, without being all dull and diagrammatical about it. So there.

...Having said all that, some of these illustrations are still pretty gruesome. Phillips' Rhamphorhynchus (above) is arguably not as extreme as William Stout's Quetzalcoatlus, but still resembles a nightmarish phantasm, a pitch-black, skeletal wraith ready to descend from the skies with an unearthly screech and peck Daniel Radcliffe's eye out. Rhamphorhynchus (is that really how you spell it?) was rather scary-looking anyway, what with its jagged array of grotesque, jutting teeth. Nevertheless, in the world of palaeoart at least, it has tended to come a distant second in the freakiness stakes to a certain big-bonced basal pterosaur found by Mary Anning...

...Except in this case, where Dimorphodon actually has rather a sad air about it. It's those cow-like chops, but more than that, it's that gaze - a wet-eyed look of wearisome resignation. Life just ain't fair if you're a sunken-headed pterosaur in an out-of-print children's book. Although clearly upset about its general appearance, the bat-like black colour scheme actually looks rather slick; as Christian Bale would tell you in between screaming at film crew, everything looks better in black. (Of course, my own tendency towards sombre attire might, er, colour my views, somewhat.) The fur is noteworthy - in spite of their rather emaciated appearance in the illustrations, pterosaurs are not described as panda-like evolutionary failures in this book. Rather, they are declared to be likely warm-blooded, active, and relatively intelligent.

But brains or no, pterosaurs do have an alarming tendency to end up as somebody's lunch in TMWoD. This particularly applies to Pteranodon, which not only seems to fly directly into a tyrannosaur's mouth on the cover, but is later caught unawares by a very Knightian mosasaur. Phillipps' skill with a brush comes to the fore here, as the swirling, tumultuous seascapes are quite beautifully painted. Given the artists' obvious talents in this area (and, er, rather similar works by Burian and Knight), the following piece seems, quite happily, inevitable...

LET THEM FIGHT! It's the classical scene of crest-backed mosasaur versus impossibly snake-necked, rearing elasmosaur; a retrospectively silly palaeoart trope that nevertheless produced some brilliantly exciting artwork. Like this. Phillipps can't top Burian's more realistic and well-informed approach, but this is still a wonderfully lively and engaging piece - from the furious vortex of the waves, to the creatures' bloody wounds reflecting the crimson sky. This painting, we now know, is fantastical...but you've got to love it anyway.

The illustration that's aged perhaps the most gracefully also features a marine reptile, namely Nothosaurus. No doubt it's not entirely correct (those eyes don't look to be in quite the right place, for one), but the body plan is there, as are the snaggly teeth, correctly showing variation in form. Most importantly*, it's very beautifully painted, with a naturalistic approach that seems to be missing from many of the dinosaurs in this book - maybe because they were thought of more as 'monsters'. I particularly like the eye. Reminds me of pigeons.

Similarly well-painted is this Ornithosuchus. The book follows the once-popular idea that this animal was ancestral to theropods, and the illustration makes the animal appear more theropod-like than it likely was (even if certain Triassic pseudosuchians really did end up looking quite theropodesque). In spite of any inaccuracies, this plate is highly evocative in placing the animal in a very naturalistic-looking environment. It just goes to show that, even when they don't really know the animals they're portraying, decent artists can still pull through in the end. (Whereas Pixelshack never will. Give it up, DK.)

And finally...over on our Facebook page, Fabian Wiggers asked if this post would feature "that duckbill leaning against a tree in an awkward way and trying to chew a droopy branch". Well, here it is. After being all effusive about those other pieces (or at least, I probably was from the point of view of marine reptile bods), I'll have to shrug my shoulders and admit that this one's pretty bad. It's retro in the worst, 'let's copy other artists and insert generic backgrounds and vague trees!' kind of way. It's brown and dull and wrinkly and blah.

Of course, it could be worse.

*What can I say? When I drink, I betray myself.

Now let's be fair - depicting pterosaurs in dessicated, mummy-like fashion was commonplace at the time this book was produced. Contemporary mass estimates had giants like Pteranodon weigh about the same as the shrivelled walnut that sits between Ken Ham's ears. In order to make sense of this, life restorations had to be stripped of all but the most essential bodily tissues, and occasionally even of those. Phillipps' Pterodactylus (above) is not an aberration, but the norm - right down to the erroneous dangling bat-posture. As it happens, I believe this is a rather effective plate - it's striking, nicely composed, and shows the animal's key attributes and overall form rather nicely, without being all dull and diagrammatical about it. So there.

...Having said all that, some of these illustrations are still pretty gruesome. Phillips' Rhamphorhynchus (above) is arguably not as extreme as William Stout's Quetzalcoatlus, but still resembles a nightmarish phantasm, a pitch-black, skeletal wraith ready to descend from the skies with an unearthly screech and peck Daniel Radcliffe's eye out. Rhamphorhynchus (is that really how you spell it?) was rather scary-looking anyway, what with its jagged array of grotesque, jutting teeth. Nevertheless, in the world of palaeoart at least, it has tended to come a distant second in the freakiness stakes to a certain big-bonced basal pterosaur found by Mary Anning...

...Except in this case, where Dimorphodon actually has rather a sad air about it. It's those cow-like chops, but more than that, it's that gaze - a wet-eyed look of wearisome resignation. Life just ain't fair if you're a sunken-headed pterosaur in an out-of-print children's book. Although clearly upset about its general appearance, the bat-like black colour scheme actually looks rather slick; as Christian Bale would tell you in between screaming at film crew, everything looks better in black. (Of course, my own tendency towards sombre attire might, er, colour my views, somewhat.) The fur is noteworthy - in spite of their rather emaciated appearance in the illustrations, pterosaurs are not described as panda-like evolutionary failures in this book. Rather, they are declared to be likely warm-blooded, active, and relatively intelligent.

But brains or no, pterosaurs do have an alarming tendency to end up as somebody's lunch in TMWoD. This particularly applies to Pteranodon, which not only seems to fly directly into a tyrannosaur's mouth on the cover, but is later caught unawares by a very Knightian mosasaur. Phillipps' skill with a brush comes to the fore here, as the swirling, tumultuous seascapes are quite beautifully painted. Given the artists' obvious talents in this area (and, er, rather similar works by Burian and Knight), the following piece seems, quite happily, inevitable...

LET THEM FIGHT! It's the classical scene of crest-backed mosasaur versus impossibly snake-necked, rearing elasmosaur; a retrospectively silly palaeoart trope that nevertheless produced some brilliantly exciting artwork. Like this. Phillipps can't top Burian's more realistic and well-informed approach, but this is still a wonderfully lively and engaging piece - from the furious vortex of the waves, to the creatures' bloody wounds reflecting the crimson sky. This painting, we now know, is fantastical...but you've got to love it anyway.

The illustration that's aged perhaps the most gracefully also features a marine reptile, namely Nothosaurus. No doubt it's not entirely correct (those eyes don't look to be in quite the right place, for one), but the body plan is there, as are the snaggly teeth, correctly showing variation in form. Most importantly*, it's very beautifully painted, with a naturalistic approach that seems to be missing from many of the dinosaurs in this book - maybe because they were thought of more as 'monsters'. I particularly like the eye. Reminds me of pigeons.

Similarly well-painted is this Ornithosuchus. The book follows the once-popular idea that this animal was ancestral to theropods, and the illustration makes the animal appear more theropod-like than it likely was (even if certain Triassic pseudosuchians really did end up looking quite theropodesque). In spite of any inaccuracies, this plate is highly evocative in placing the animal in a very naturalistic-looking environment. It just goes to show that, even when they don't really know the animals they're portraying, decent artists can still pull through in the end. (Whereas Pixelshack never will. Give it up, DK.)

And finally...over on our Facebook page, Fabian Wiggers asked if this post would feature "that duckbill leaning against a tree in an awkward way and trying to chew a droopy branch". Well, here it is. After being all effusive about those other pieces (or at least, I probably was from the point of view of marine reptile bods), I'll have to shrug my shoulders and admit that this one's pretty bad. It's retro in the worst, 'let's copy other artists and insert generic backgrounds and vague trees!' kind of way. It's brown and dull and wrinkly and blah.

Of course, it could be worse.

*What can I say? When I drink, I betray myself.

Tuesday, July 15, 2014

The TetZooCon was on

So, TetZooCon 2014 happened, and you won't hear a bad word said of it among those of us who attended. The event was a spin-off of the incredi-popular Tetrapod Zoology blog, authored by fish-hating mega-brain Darren Naish, and also the similarly named podcast, hosted by Darren and partner in tapir in-joke crime, John Conway. I'm sure neither will need an introduction around these parts; suffice it to say, the event reflected the incredibly diverse range of topics discussed on the blog and podcast, ranging from Dougal Dixon future-bats to false azhdarchid head nubbins, and from mermaids made from papier mach� and string to having a seabird land on one's head. And there was a quiz. And it was bonkers. But more on that shortly. (All photos by Niroot.)

I'm afraid to say that I didn't have my onetime-coulda-been-a-journalist hat on for this one; quite apart from the fact that it doesn't fit very well any more, I'd paids my money and the choice I tooks was to sit back and enjoy the show. Therefore, I'll be taking the lazy option and basing my (brief) report on the schedule we were all given. I'm sorry. Sorta.

The Con was held at the London Wetland Centre, and opened with a talk from Darren himself on speculative zoology - its history and why we should give a flying flish about it. In doing so, he drew upon distinct strands of speculative zoology, including horrifying visions of the future, making (scientifically informed) shit up about the past, and inventing alternative timelines in which sapient iguanas won World War II. A personal highlight was a look at the work of Dougal Dixon, whose speculative zoological works included dinosaurs that (more-or-less) have since been discovered, silly dinosaurs, the aforementioned flightless bats, and Man After Man, which is not discussed in polite society. Darren also pointed out how, in spite of its apparently 'nitch' appeal, speculative zoology has proven to be incredibly popular; this prompted perhaps the most in-jokey slide of the show, which got a hearty chuckle from the audience. Here's looking at you, Raven Amos.

Darren's talk was followed by Mark Witton's, and the pair gave each other high-fives as their giant medallions swung about their necks (no, not really). Mark was there to discuss the history of research on azdarchid pterosaurs, they of the huge heads, wing spans and, of late, media presence. In doing so, he illuminated the thinking behind a number of palaeoart memes related to these animals, and Quetzalcoatlus in particular (a topic that has been covered on the Tet Zoo blog). Perhaps most notable for readers of this blog, we saw how a very brief paper on bits-and-pieces of pterosaur resulted in illustrator Giovanni Caselli tasked with drawing an animal that was 'really honkin' big', and otherwise left to his own devices. And so, the pin-headed nightmare monster was born. Later came Sibbick's Quetzalcoatlus, itself (like everything else by Sibbick, ever) copied endlessly in spite of mistakes borne of misinterpreted material.

The following two talks both concerned cryptozoology - a recurring subject on the blog, and also tying in neatly, of course, with the Cryptozoologicon Volume 1, which Darren and John worked on alongside Memo Kosemen. Paolo Viscardi's hugely entertaining history of 'Feejee' mermaids revealed how meticulous scientific analysis can yield surprising results from even obviously fake specimens. Long thought of as 'monkeys sewn to fish', it only took a cursory examination of the teeth to show that this most certainly wasn't the case - they had fish jaws! In fact, while the lower half (or at least the outside) was indeed a fish, the top half of each 'mermaid' - as revealed by CAT scanning - was composed of whatever odds and ends the manufacturers had to hand, including paper, wood and even balls of string. As revealed by Paolo, gullible Europeans parted with unimaginably huge sums of money for these forgeries, and - thanks to PT Barnum famously getting his hands on one - there are now forgeries of forgeries. Of course, there was also a look at the history of mermaids in folklore throughout the world, which gave the talk an intriguing anthropological bent.

Similarly, Carole Jahme's talk - 'Was Caliban an Orang Pendek?' - was a concise, but thorough, look at the history of legendary 'wild men', supposedly happened upon by European explorers in Southeast Asia. So authoritative were such accounts, Linnaeus saw fit to include the likes of 'Homo sylvestri' in his Systema Naturae, albeit under the 'Paradoxa'. The title alluded to the notion that, given that Shakespeare moved among the circles of explorers, sailors and scientists, and often incorporated the latest scientific ideas into his plays, perhaps it wouldn't be too fanciful to suppose that Caliban was inspired by accounts of 'ape men' cryptids from exotic lands.

Then there was lunch, with fine company and a nice, cool beer. My first of many that day (I'm like that when I get chatty).

The beer was a tough act to follow, but Helen Meredith did an admirable job. Her talk posed the question: "What have amphibians ever done for us?" (Yes, there were Monty Python references.) Determined to convince us of the worthiness of the squishy-skinned ones, Helen made the case on several very important grounds. They're an important part of countless ecosystems throughout the globe, of course, and they're far more diverse and crazy than many people realise - ranging from terrifyingly gigantic Japanese giant salamanders to minuscule, limbless caecilians, which excite the herpy types no end (as Helen demonstrated with photos of herself and colleagues in the field). But there's more - we can still learn so much from amphibians that can be applied, in particular, to the field of medicine. Of course, there was also a highly entertaining sojourn into the world of frogs secreting psychotropic substances from their skin. You know, licking toad, man. All in all, brilliant stuff.

You'd be forgiven for thinking that Mike Taylor (of SV-POW!) was tripping on frogs when he was reeling off facts and figures pertaining to the awesomeness of sauropod necks, but then such is the ridiculous massiveness - and neckiness - of those most preposterous of dinosaurs. Mike was there to reveal the secrets of sauropods' success; a combination of a big, sturdy gut-platform, a small head, an efficient, avian-like respiratory system, and highly specialised (and numerous) neck vertebrae. It's something that mammals, limited as they are by their evolutionary inheritance, will never manage - even if Mike conceded that giraffes do a pretty good job given their unfortunate circumstances. Oh, and he apologised again for the whole Giraffatitan thing. He hates the name, you know, but what can ya do...

Dinosaurs continued to dominate in the palaeoart workshop, during which the audience - along with artists Mark Witton, Bob Nicholls, and John Conway - were asked to fashion a life restoration from a jumbled set of bones. With scientists in the audience chipping in with additional anatomical info, the three palaeoartists were able to conclude that the creature was an archosaur with long, sturdy hind limbs and a fat behind, but nevertheless came up with three very different imagined creatures.

And no wonder - the illustration they were working from was of the Mantell-piece. Of course, quite a number of people in the audience realised this (including me), and consequently handed in any number of variations on an 'old-school Iguanodon'. And yeah, I contributed one of them. I'm a git.

Photographer Neil Phillips was next, and what a treat he had in store - a series of stunning photos and videos of British wildlife, with all the entertaining anecdotes to match. Neil's been climbing around rocky islands, scrambling about in the darkness, freezing his arse off in a hide in the depths of winter, had birds run at him, attack him and land on his head, and smugly beat fellow photographers with expensive kit to the best shot. What a guy.

Then there was the quiz. The first question was easy - Tyrannosaurus rex, duh. Then it got difficult. Then it got stonkingly difficult. Niroot and I bashed our heads together and managed to walk away with third prize. First prize - a domestic pig skull - went to Kelvin Britton, who managed a frankly absurd 23 out of 30, the swine (djageddit?), while Richard Hing took second. The quiz ranged from the generic names of plesiosaurs, to shrews, to crocs, to bats, to whatever the hell the 10,000th comment on the blog was. (I still can't remember.)

And finally - we went on a tour of the wetland centre. Then went to the pub, where I probably had one too many. You can't blame me - they had Fuller's ESB on cask. Fantastic beer.

To conclude; a wonderful time was had by all, and I'd sincerely like to thank Darren, John and everyone involved in organising the day, not to mention everyone who put up with my inebriated ramblings at the pub. It was a rewarding day, I met wonderful people, and I hope to see even more there next year. (Oh yes, there'd better be a next year!)

|

| Darren Naish |

I'm afraid to say that I didn't have my onetime-coulda-been-a-journalist hat on for this one; quite apart from the fact that it doesn't fit very well any more, I'd paids my money and the choice I tooks was to sit back and enjoy the show. Therefore, I'll be taking the lazy option and basing my (brief) report on the schedule we were all given. I'm sorry. Sorta.

The Con was held at the London Wetland Centre, and opened with a talk from Darren himself on speculative zoology - its history and why we should give a flying flish about it. In doing so, he drew upon distinct strands of speculative zoology, including horrifying visions of the future, making (scientifically informed) shit up about the past, and inventing alternative timelines in which sapient iguanas won World War II. A personal highlight was a look at the work of Dougal Dixon, whose speculative zoological works included dinosaurs that (more-or-less) have since been discovered, silly dinosaurs, the aforementioned flightless bats, and Man After Man, which is not discussed in polite society. Darren also pointed out how, in spite of its apparently 'nitch' appeal, speculative zoology has proven to be incredibly popular; this prompted perhaps the most in-jokey slide of the show, which got a hearty chuckle from the audience. Here's looking at you, Raven Amos.

|

| Mark Witton |

|

| Paolo Viscardi |

|

| Carole Jahme |

Then there was lunch, with fine company and a nice, cool beer. My first of many that day (I'm like that when I get chatty).

|

| Helen Meredith |

|

| Mike Taylor |

|

| The workshop - the audience could view the artists' progress on-screen. L-R: MC John Conway, Mark Witton, Bob Nicholls. |

|

| Niroot's creation. ROTTEN CHEATER! |

|

| Neil Phillips |

Then there was the quiz. The first question was easy - Tyrannosaurus rex, duh. Then it got difficult. Then it got stonkingly difficult. Niroot and I bashed our heads together and managed to walk away with third prize. First prize - a domestic pig skull - went to Kelvin Britton, who managed a frankly absurd 23 out of 30, the swine (djageddit?), while Richard Hing took second. The quiz ranged from the generic names of plesiosaurs, to shrews, to crocs, to bats, to whatever the hell the 10,000th comment on the blog was. (I still can't remember.)

|

| Oh boy. (This photo courtesy of Darren.) |

|

| NOT THE DUCKLINGS! |

Monday, July 14, 2014

Interview: Paleoartist Maija Karala

"Forest Green." A dandy paravian, � Maija Karala and used with her permission.

I'm always excited to see new work pop up in Maija Karala's DeviantArt gallery. A Finnish biologist and writer, her enthusiasm for biology also finds voice through her illustrations, which range from fleshed out scenes to charming sketches. I can't remember exactly when I began following Maija's illustrations, but I do remember being particularly struck by her Tarpan fending off a lion.

"Don't Mess With Tarpans." � Maija Karala and used with her permission.

Maija writes:

Here, a young cave lion is about to learn why one should be careful with tarpans. It's July somewhere close to the edge of the ice and the steppe-tundra is blooming. The plants depicted include Betula nana, Viscaria alpina, Rhododendron lapponicum, Orthilia secunda, Pedicularis sceptrum-carolinum and Dryas octopetala. Yes, the latter is the plant that was so common at the time at gave its name to the Dryas climatic periods.It's a great example of the qualities I admire in much of her work: a sense of drama, subtle and naturalistic color, dedication to research, all wrapped up in an eminently approachable aesthetic. I was happy when Maija agreed to do an interview for Love in the Time of Chasmosaurs, so I could ask her more about how she works.

What is your background as an artist? Is it your profession or hobby?

For me, art is mostly a hobby. I make my living as a science writer, mostly writing for newspapers and magazines. I do paid illustrations whenever I get a chance, but it's not very often. I'd love to do more of it, but the fact that I always thought it as just a hobby now hinders me a bit. As I haven't really practised my skills systematically, I only became good at the things I like doing.

"Hamipterus." � Maija Karala and used with her permission.

Do you get many opportunities to cover paleontology in your science writing?

I get to cover paleontology fairly often, though not as often as I'd like. A few articles per year or so. On my blog (which is unfortunately in Finnish, but can be found at http://planeetanihmeet.wordpress.com/) I do write a lot about paleontology and use my own illustrations as well.

Do you plan on continuing to do illustration as a hobby, or do you have professional aspirations?

I'm working to become a better artist, and I'd love to do more professional illustrations too. Though writing is probably still going to be my main occupation.

Was illustrating extinct animals always something you did or did you come to it later in life?

I drew dinosaurs as a kid, like everyone else, but stopped somewhere in my early teen years and only started again when I began my university studies, seven years ago (I studied biology). During the gap, I mostly drew fantasy creatures, dragons and elves and stuff. I think the main reason I started making paleoart was to find sort of a compromise between drawing fantasy creatures and being a science student. Illustrating extinct animals is firmly rooted in science, but also lets you use your imagination in a way not really possible with bioillustration.

"Eye Contact." Anurognathus ammoni, � Maija Karala and used with her permission.

At what point in an illustration do you focus on the eyes? It's often a striking element in your work, whether fantasy or paleoart.

I have never really thought about that. I do tend to think the eyes and expressions as the most important part of my drawings, as that's also what I pay the most attention when looking at live animals (or people, for that matter). Though I have no idea if everyone else does that too. After making a general sketch on what I want there to be and where, the eyes (or the facial areas in general) are usually the first thing I focus on.

You seem to be especially drawn to feathery theropods. Is this due to a bird interest or is there some aspect of their form that is especially fun to draw?

I think it's a bit of both. I like birds, sure. I also like drawing small and pretty animals. And feathers are always fun. Anyway, the main reason is probably that there's plenty of references and easily accessible knowledge available on feathered dinosaurs. It was an easy place to start back when I started making paleoart, and once I was familiar with them, it was also easy to continue.

Lately, I have been moving on to other critters as a part of trying to learn new things. My DeviantArt gallery is now starting to have more things like fossil mammals and non-dinosaurian archosaurs than feathered theropods on the first pages.

When illustrating an animal that has been covered by other illustrators, in what ways do you try to make it your own?

I always try to find other sources of inspiration besides other people's depictions of the same animal, sometimes actively avoiding looking at them when planning to make my own reconstruction. I often look up modern animals with somewhat similar ecology and use their soft tissues and behaviour as inspiration, but try never to directly copy anything. I mostly avoid using the most obvious colour themes or soft tissue ideas. That's not to say I never stumble on paleoart memes, but I do try to avoid it.

"The Feathered Yeti." Xiaotingia zhengi, � Maija Karala and used with her permission.

How much do comments on dA influence your work? For instance on your "Feathered Yeti," the comments get into some serious detail about integument. When posting work do you post with the expectation that you'll receive critique on areas you're not sure about?

To be honest, DeviantArt comments have probably been the most important thing pushing me to get better at making paleoart. These days I usually do my research before drawing, but especially earlier it was a great motivator to make embarrassing mistakes and get someone tell it to me. I'm pretty sure I never made the same mistake twice.

As I have mostly learned paleontology and anatomy on my own (for years, I had no paleontologically oriented friends nor any education on either subject), the criticism has been invaluable. I still greatly appreciate all the experts who go through the trouble to nitpick on amateur drawings.

"I Immediately Regret This Decision." Thalassodromeus attempting to eat Mirischia, � Maija Karala and used with her permission.

So, who are some of your favorite expert paleoartists? Is there a particular piece of advice or critique you received that has stuck with you?

I really like the works of people like Alain B�n�teau, Ville Sinkkonen, Carl Buell and Mauricio Anton, just to mention a few. My favourites are the people who can combine an expert understanding of science with truly beautiful art and get the animals to really come to life. I also really like Niroot's style. And John Conway's. And... ok, I'll stop here before the list becomes ridiculously long.

I don't think there's any particular piece of advice that has been especially memorable. It has been more about the general message that I need to know more. It's something I simply didn't get elsewhere for most of the time. As nobody I knew personally had the expertice to tell me the feet of my Quetzalcoatlus are wrong, most feedback was more like "oh, a nice dinosaur. What do you mean it isn't a dinosaur?".

Thank you to Maija for answering my questions - and patiently waiting for me to have time to put the post together! I hope you'll stop by her DeviantArt gallery and leave some support and constructive criticism on her illustrations. Also check out the recent post at i09 featuring Maija's Protoceratops/ Griffin illustration.

"Go Home, Evolution." Atopodentatus, � Maija Karala and used with her permission.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)