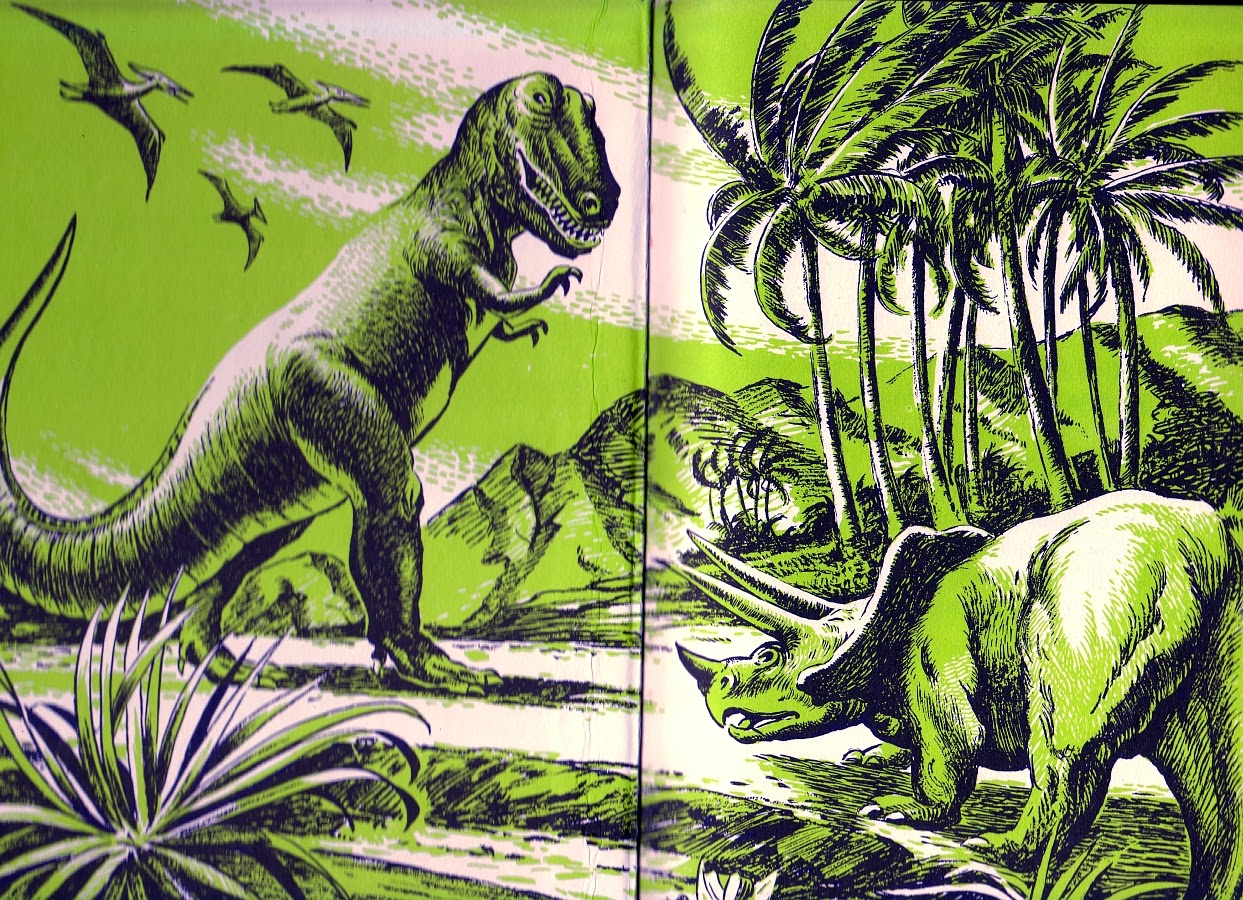

While the cover depicts a theropod that is presumably Allosaurus (based purely on the fact that it has three fingers and is quite large, which is enough to go on for most books of the period), Sexy Rexy manages to appear twice before the title page. The cover's pretty enough, but it certainly can't match the Tyrannosaurus v Triceratops piece below for visual impact - the composition effectively emphasising the towering height of old-school Nonsense Rexy, who seems to be chuckling quietly to himself. I love the palm trees, too - it seems that we rarely see strong winds in palaeoart, and they add that extra dash of drama. Poor Triceratops ends up looking rather lumpen and misshapen here, rather than a well-matched opponent a la Knight. One can't help but imagine the T. rex rolling it along with one foot like a barrel.

The book's second T. rex illustration is a more straightforward depiction of the animal in lateral view (or everything but the tail, anyway), and seems to be inspired by the old T. rex mount at the American Museum of Natural History. An amphibious (or, let's be fair, just swimming) sauropod adds some interest. But we all know what we're here to see.

Deadly dinosaur duels! Rather than play fair and pick on something with its own pointy things with which to defend itself, Rexy here sinks his teeth into "fat, hulking" "Trachodon", the unfortunate, web-handed fodder du jour. Still, the flipper-fingered one does at least put up something of a fight, albeit a half-hearted one:

"There is frantic thrashing for a time as the colossal beasts roll in the slippery muck. Then the Trachodon lies still. Its head hangs loosely, almost severed from the neck by six-inch teeth."Ouch. Still, what a way to go - at the waggling atrophied forelimbs of "the most terrible creature of destruction that ever walked upon the earth!" (Don't be silly, Roy - everyone knows that's humans. Yeah, take that, conspecifics!)

Just lovely stuff. You can't beat an old-fashioned, salivating description of reptilian behemoths having at it, even if the illustrations are a little more convincingly bloody these days.

Happily, hadrosaurs aren't just depicted as an easy lunch in All About Dinosaurs. As is typical of a mid-20th-century work, they are imagined to have been amphibious and depicted as such, with their crests imagined as aqualungs (a concept so screamingly silly, only a pre-1960s palaeontologist could possibly have thought of it). The creatures do suffer a little from the 'gangly dork hadrosaur' meme that was popular into the 1970s, but I do still love the depiction of Corythosaurus contentedly doggy-paddling its way through a lake (below). There's some great characterisation going on here too - it's possible to sense the furtiveness of the foreground individual, frond in beak, as it glances to the shores where tyrannosaurs might be lurking.

If there is one creature that looks truly, irredeemably derpy, even for the standards of the time (forget not the great work of Burian), it is this unfortunate slug-bottomed monstrosity masquerading as ornithopod pin-up Iguanodon. On the other hand, I have the strangest feeling that this illustration has been 'inspired' by another, although I can't find it for the life of me; reader assistance would be most welcome.

While Stegosaurus fares considerably better in the illustration department, it is once again the recipient of much mockery aimed at its apparent brainlessness. Speculating on why the dinosaurs went extinct, Andrews posits that their tiny brains may have played a part; after all,

"In Stegosaurus, which must have weighed four or five tons, the brain was no larger than that of a small kitten. With such a brain, the animal could barely eat and sleep and muddle through life. The Thunder Lizard and the other great sauropods were not much better off in brain capacity."

While it's fun to have a giggle at what are to us, all the way over here in Space Year 2014, amusingly outmoded concepts, it's worth noting that Andrews, unlike his contemporaries, did not view dinosaurs as evolutionary failures. In fact, he is dismissive of the notion that dinosaurs were the victim of "racial senescence", or basically just being too long-in-the-tooth (so to speak), and is quick to point out that a panoply of animal clades snuffed it at the end of the Cretaceous, not just dinosaurs.

Of course, a refusal to accept that dinosaurs were the result of Evolution's Difficult Middle Years doesn't prevent Andrews from occasionally being a bit unkind toward them, albeit in a rather tongue-in-cheek manner. This is perhaps best exemplified in the caption for the illustration below, which happens to depict a creature named after him. In the text, Andrews describes P. andrewsi thusly:

"...he was one of the ugliest of all the small dinosaurs. His short, toad-like body seemed to be mostly head. A piece of bone from the frill projected downward on each side of his face. It looked like a long wart. His short legs were badly bowed. The tail was fat and thick. He crawled on his belly. No leaping or running for him...No, I can't be proud of his looks."Andrews' delicious description of Protoceratops, in addition to Voter's accompanying illustration, probably helped cement the image of the ceratopsian as a sprawling fatty even into the 1990s. Modern depictions are rather different, but Andrews' unflattering portrait of the animal still raises a smile.

Of course, Andrews is keenest on mentioning Protoceratops in connection with eggs - he was the man who famously discovered the first dinosaur eggs, after all. Unfortunately, Voter's Protoceratykes are quite terrifying - rather than lacking frills (as Andrews describes them), their faces appear to be entirely frills, with eyes and a beak bolted on. The foreground individual reminds me of Mr Sweet from the Doctor Who episode The Crimson Horror. That beak...brrrr.

Next time: more Andrews/Voter! Hooray.